Over the course of her career, Jamie Lee Curtis has received an Academy Award, a BAFTA, two Screen Actors Guild Awards, and two Golden Globe Awards. Her work in a plethora of horror films — among them, Prom Night, The Fog, Virus, and of course, numerous installations of the Halloween franchise — has earned her the title of “Ultimate Scream Queen.” Her cameo appearance in season two of The Bear was a highlight of the already fantastic series, and her 2023 Oscars acceptance speech for Best Supporting Actress in Everything Everywhere All at Once was a joyful tribute to the many people who have helped her along her journey. And yet, what some people may not know is that in addition to her 46-year acting career, Curtis is a New York Times best-selling children’s book author.

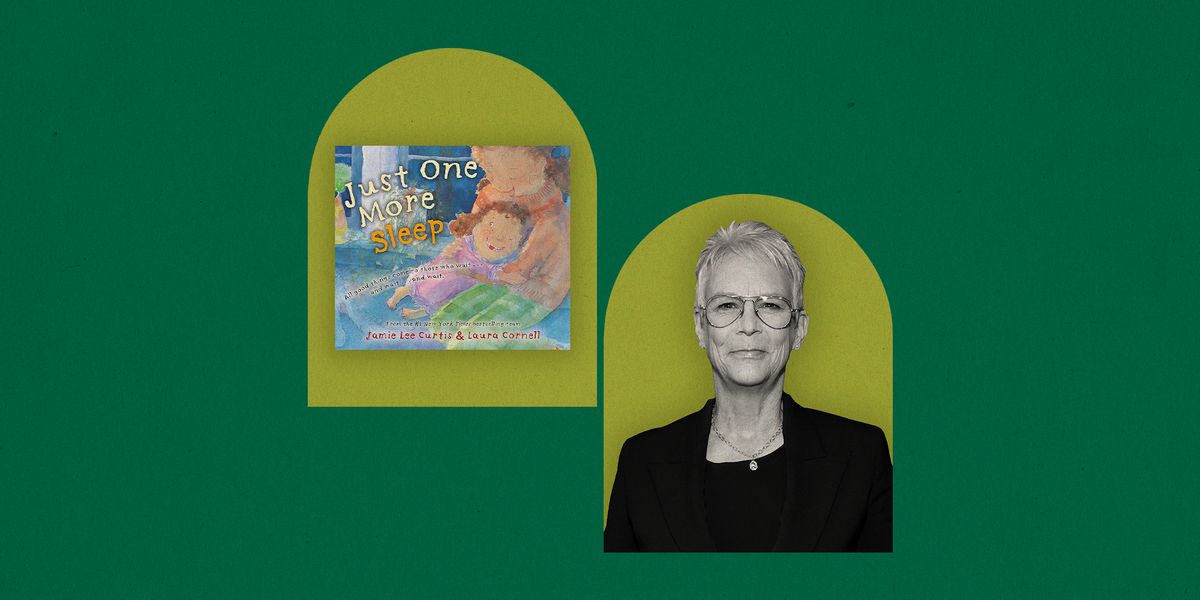

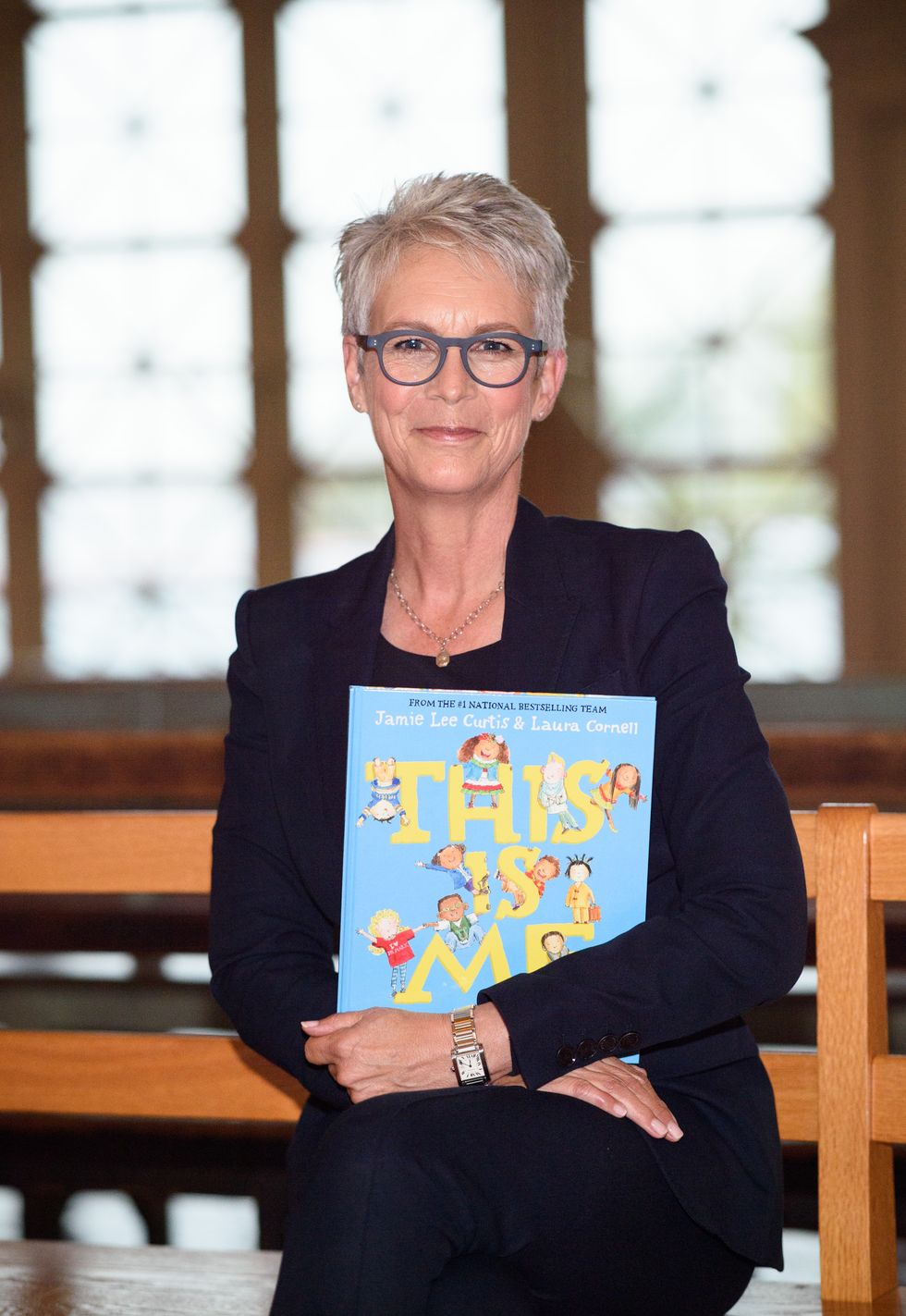

Since her debut 1993 book, When I Was Little: A Four-Year-Old’s Memoir of Her Youth, Curtis has published a total of 13 children’s books, as well as a graphic novel, Mother Nature, based on her script of the same name. Now, she’s promoting her latest picture book, Just One More Sleep: All Good Things Come to Those Who Wait … and Wait … and Wait. Featuring illustrations by her longtime collaborator Laura Cornell, the book is a reminder to children that patience is a wonderful virtue, particularly when it comes to exciting holidays and events.

Curtis tells Shondaland that when it comes to writing, she doesn’t have a master plan for her books but instead waits for them to come to her. Speaking about her 1998 book Today I Feel Silly: And Other Moods That Make My Day, she says, “I had this idea of a book called My Mood Swing — it popped into my head and made me laugh. There was a swing that a child gets on, and one day it’s in a good mood, and one day it’s in a bad mood. I tried to intellectualize it, and it was not working. I couldn’t figure it out. A friend of mine and her brother came over, and he said, ‘Are you working on another book?’ I said, ‘Yeah, I had this idea about a mood swing, and I haven’t cracked it yet. I mean, it just needs to be simple, right? It really needs to be, “Today I feel silly. Mom says it’s the heat. I put rouge on the cat and gloves on my feet. I ate pancakes for breakfast and,” you know, whatever.’ And in that second, the book presented itself, and it presented itself in rhyme. I went in the other room and wrote the book. That’s how these books come out of me. I’m waiting for them. They show up when they show up.”

On a video call from her home, Curtis spoke with Shondaland about her writing career, book bans, and why she’ll never publish a memoir.

SANDRA EBEJER: I’ve read past interviews where you’ve said you never planned on writing books of any kind. Now that you have well over a dozen books to your name and you’re a New York Times best-selling author, how do you feel about the trajectory your career has taken?

JAMIE LEE CURTIS: I never expected I would write books. It was an unexpected career I didn’t even think would be a career. The lucky thing for me is that it’s a career based on passion and only comes when the muse hits me. I am not required to churn out a book [after a specific] period of time. It turned out that I ended up being quite prolific, and I was able to make a book every two years for a long period, but I didn’t have to rely on it for my financial life. I felt no pressure whatsoever. If the book came, it came. It was always out of a situation with a child that the book was born.

For instance, there’s a book that I wrote called Where Do Balloons Go? An Uplifting Mystery, which was born at a children’s birthday party. We took shelter at a public park under a gazebo because a storm came through and the sky got very dark. The party favors for the birthday were going to be one helium balloon for each kid, and they were all tied to a pole of the gazebo. As we were huddled, a little boy was playing with the string that was holding them there, and he untied the string, and they all shot out into the air. You can imagine the dark gray sky and these crayon-colored balloons and that audible moment where everyone in the group — there were probably 10 parents and 10 kids — went [makes a loud gasp]. And a little girl was standing next to her mother, and she pulled on her mommy’s sweater and said, “Mommy, where do balloons go?” In that second, it was like I had been struck by lightning. I went home and wrote a book. That book came out of me that fast because that’s the miracle of both creativity and imagination for children.

This new book was born December 24, 2020. I was out on the street getting my mail, and [my neighbor] Betty and her mom were taking a walk. I saw them, and I was like, “Hey, Betty! Santa’s on his way!” And she went, “No, Jamie! One more sleep, then Santa.” And in that second, I realized, “Oh, right! Children metabolize time through sleep.” And the book wrote itself that day.

SE: Since writing wasn’t in the plans, when you wrote your first book, did you have any trepidation or a sense of impostor syndrome?

JLC: No. Because I didn’t write it; it wrote itself. My 4-year-old marched into my room and said, “When I was little, I wore diapers. Now I use a potty!” And she marched out of the room. I had a pad on my desk. I laughed, and I wrote down, “When I Was Little: A Four-Year-Old’s Memoir of Her Youth.” What she was saying is that she had a past. Four years is high school. Like, the entirety of high school, my daughter’s been alive. But I’d never thought about it that way because she just looked like a little kid. All of a sudden, I went, “Oh, wait. She had a life.” And so, I wrote a list of things — I was making myself laugh — like “When I was little, I didn’t know I was a girl. My mom told me.” I made myself laugh a bunch. And at the end, I wrote three things, and I started to cry. I wrote, “When I was little, I didn’t know what a family was. When I was little, I didn’t know what dreams were. When I was little, I didn’t know who I was. But now I do.” In that moment of realization that my daughter knew who she was? Sobbing. It was only in that moment that I knew it was a book. When I was writing the list, I didn’t know it was a book. When I was writing the list, it was just a list of funny things. When I started to cry, I went, “Oh, wow. This is a book for children.” And that’s how it was born. So, there is no impostor syndrome because I am not pretending to be a writer. I just am.

SE: Does your work as an actor ever influence your work as a writer, or vice versa?

JLC: The only requirement is that it moves me. I think life is hard. I think being a child is hard. I think I understand that. And from an emotional human being standpoint, I feel like I have to connect to the real complication of being human, even when you’re 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 [years old]. As long as I hit that note emotionally, I know it’s a good book. There’s one of my 15 [books] that I feel like I kind of wrung the emotional washcloth a little trying to get there. You know what I mean? Like, I feel like I forced the emotion a little bit. But five or six of these books, I cry every time I read them. Every single time I read them, I cry because they move me. And in the moving me, it made me realize “I’m right in the emotional zone of being a child.” I’m a highly tuned emotional person. And so, my books have to move me, and once they move me, it lets me know “You’re fully in the zone. You’re telling the truth.” Because again, I’m not a [does air quotes] writer.

SE: That said, you’ve also written a graphic novel that was based on a screenplay that you wrote.

JLC: I’ve written a screenplay that ultimately became a graphic novel, and I’ve written short stories that I’ll never publish. I have too much respect for great writing to ever publish anything [like that]. I will not write a memoir. I’m not going to do that. I don’t need to do that. I may write something — like, I may write an essay that’ll get published when I’m dead — just to be able to set some records straight so that I have that last word. But I won’t do it while I’m alive or while my family is alive because the problem I have with memoir is that it requires you to share intimate, very personal interactions with other people. I have had people that I was intimate with write books, and I was petrified as to what they would divulge. I really appreciate all of my friends who’ve written books. I feel like they’ve done so in a really beautiful, truth-telling way. And yet, I think there are moments where they’ve had to confront the fact that they’ve shared something very personal and private with strangers. And I’m not going to do so.

SE: I interviewed your friend John Stamos and loved the foreword you wrote for his memoir.

JLC: The beautiful part of John’s book is that he pulls [off] the Band-Aid from the first page. He gets right to it. It’s a very honest book. His book is much more an appreciation of his life rather than a distillation of personal issues. Each person who writes an autobiography has that looking-in-the-mirror moment where they’re going to look in the mirror and understand that it’s their story to tell. We each have our own story to tell. I very much appreciate people’s need to do that. I’m not going to do that.

SE: What advice would you give to someone who aspires to write children’s books?

JLC: The beautiful thing about human beings is we can all do anything. Aspire? Just write. My husband [Christopher Guest] is an artist and musician and an actor, and he has people say to him, “I’m thinking about learning how to play the guitar.” And he’s always like, “There is no thinking about learning how to play the guitar. You just want to learn how to play the guitar, and you do everything you can to learn it.” That’s passion. That’s the beautiful part of having an independent mind — not a calcified mind, not our parents’ minds, not our government’s minds. John Steinbeck, who wrote East of Eden [and is] my favorite writer, writes this beautiful thing about how the free, roving mind of the human being is the most important thing to protect against, as he refers to it, “the stunning hammerblows of conditioning.” If we can have our own mind, based on our own experiences, what we read and hear and see, then anybody can do anything. You can write because it’s from your point of view. If you’re trying to write like someone else, forget it — it’s over. But the aspiration to write is the passion to write. And everybody can write. Grab a pen, grab a paper, put it down, undirected. Just tell what’s in your head. That’s what writing is. I am a perfect example of that. I never thought I’d write a word in my life. And one day, my 4-year-old said something, and my life changed. That’s how life works. So, I say, “Attach to your passion, and let go of the result.” Because the result becomes then the goal, and that shouldn’t be the goal.

SE: I’ve been asking this question of authors lately because it’s something that I am very concerned about. We are dealing with an onslaught of book bans and challenges right now. As both a parent and an author, what do you say to those who are attempting to challenge literature?

JLC: We live in a country which is founded on the principle of freedom of speech. And that is being betrayed by a hyper-conservative, authoritarian sect. It’s all about control. And you can’t say the word “freedom” and the word “control” in the same sentence. You just can’t. You either have freedom, or you don’t. And it’s terribly alarming, but it’s just an added alarm. A lot of alarm bells are ringing because it’s a scary time where freedom is under attack — freedom of thought, freedom of religion, freedom of ideas, freedom of choice. Freedom is under attack. And the banning of books is a long-held first foray into it. If you look through history, book banning is like the first bell ring. So, it’s a time to be vigilant and active.

In Is There Really a Human Race, this little boy in the book is freaking out because it feels like everything is just a big competition. His concern is if we’re all just running and running and running, we’re all going to crash. Which is how I think we all feel right now. Are we all going to crash? Then, the mommy says to him — which is the single-handed best thing I will ever write — “Sometimes it’s better not to go fast. There are beautiful sights to be seen when you’re last. Shouldn’t it be that you just try your best? And that’s more important than beating the rest. Shouldn’t it be, looking back at the end, that you judge your own race by the help that you lend? So, take what’s inside you, and make big, bold choices. And for those who can’t speak for themselves, use bold voices. And make friends, and love well, and bring art to this place. And make the world better for the whole human race.” That is the best thing I can offer. That and then using my bold voice and bold choices. And literally practicing what I’m preaching. I try to do so on the daily.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Sandra Ebejer is a New York-based writer who has contributed to The Boston Globe, The Washington Post, Greatist, Flood Magazine, and The Girlfriend from AARP. Find her on Twitter @sebejer.

Get Shondaland directly in your inbox: SUBSCRIBE TODAY