Cases of avian influenza are increasing across Canada, government data shows, but a lack of monitoring of wild birds is underscoring the threat to humans, experts say.

Also known as the bird flu, the subtype H5N1 spreads rapidly in poultry farms due to densely populated coops. However, wild birds are being disproportionately impacted by the virus.

As of Nov. 2, approximately 7.9 million poultry birds have been impacted in Canada this year, the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) website shows.

British Columbia has the highest number of birds impacted, followed by Alberta and Quebec.

The high spread rate of the virus is causing a particularly bad year for avian flu, experts say.

Not included in that total is the estimated 2,500 wild birds that have tested positive or are suspected to be positive for avian influenza, according to the Canadian Wildlife Health Cooperative.

Influenza is deadly for poultry birds not because of the virus itself, experts say, but because of the policy around the flu in coops.

When a poultry bird has contracted a highly transmissible subtype of avian flu, all birds that have come in contact with the animal will be killed to prevent further spread, the CFIA website reads.

But with cases in wild birds, transmission is not so strictly controlled. The virus often spreads without being checked, and some experts warn it is already mutating to infect other species.

“The more the virus is allowed to circulate, the more it’s allowed to evolve and change,” said Jennifer Provencher, a research scientist in the Ecotoxicology and Wildlife Health Division of Environment and Climate Change Canada.

“This particular H5N1 is a different beast than the previous ones that we have encountered,” she told CTVNews.ca in an interview earlier this week.

BIRD FLU SPREAD IN CANADA

The latest subtype of avian flu is unlike any other scientists have seen in Canada, Provencher said.

“The H5N1 has caused such widespread mortality that I think we can pretty confidently say that within living memory, no avian influenza has affected wild birds in the same capacity,” she said.

“Just like humans, as the birds congregate on the landscape during migration, they pass it to each other – just like we would pass the flu to each other. When they go into their kind of nesting zones, they spread out in the landscape, and that transmission stops,” she said.

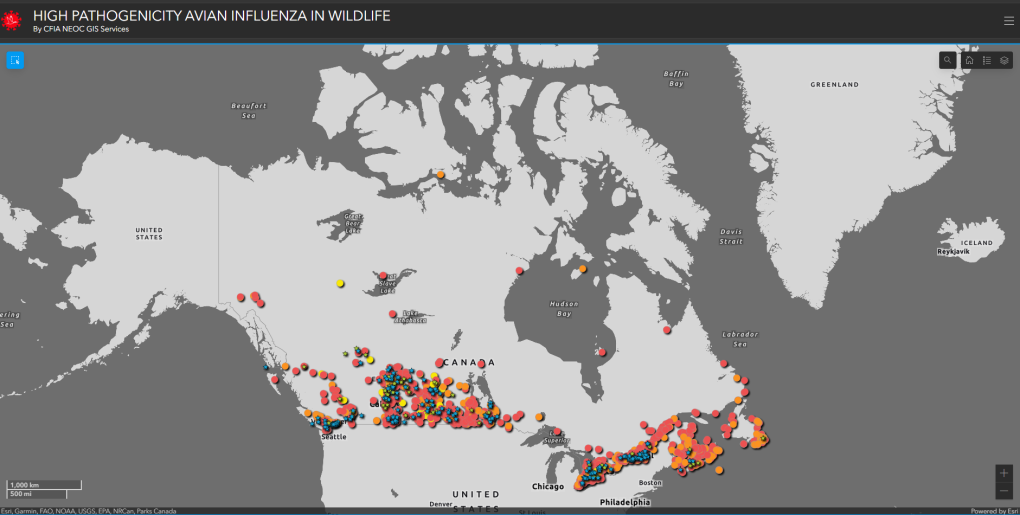

Map from the Canadian Wildlife Health Cooperative shows the number of suspected and confirmed wild birds and mammals with avian influenza. (Screenshot)

Typically the bird flu has seasons just like human influenza does, Provencher said.

A huge outbreak occurred this past spring. With cases rising in parts of Canada again, some experts say they’re preparing for another difficult season.

The virus spreads through feces and the nasal and eye discharges of infected birds, according to wildlife experts and the CFIA website.

‘INFLUENZA IS STILL THE VIRUS WE NEED TO WATCH’

Bird flu was first detected in Canada in 2004, and has a history of mutating to subtypes that can easily infect humans, such as the subtype called H1N1, which transmitted from pigs and was also known as swine flu. The H5N1 subtype is the latest mutation, and is impacting wild birds in particular.

Currently, cases of humans catching H5N1 are extremely rare, with Health Canada data showing just over 800 people worldwide have contracted the virus since 1997.

H5N1 can infect more than just birds, with cases found in foxes, skunks, cats, dogs, bears and other mammals. This shows that the virus is mutating and infecting more than just birds, Joly said, and the more animals contracting the virus, the better chance humans have at interacting with it.

“Every time a human comes in contact with an infected animal, it’s like rolling a dice…if you roll your dice more often, you’re more likely to get the winning number, or in this case, you’re more likely to get transmission to human,” said Damien Joly, chief executive officer of the Canadian Wildlife Health Cooperative, a research organization in Canada.

“This is definitely why we’re all concerned about avian influenza in birds.”

Snow geese are seen during their migratory movements at the Reservoir Beaudet, in Victoriaville, Que., Wednesday, Nov. 1, 2023. (THE CANADIAN PRESS/Bernard Brault)

Snow geese are seen during their migratory movements at the Reservoir Beaudet, in Victoriaville, Que., Wednesday, Nov. 1, 2023. (THE CANADIAN PRESS/Bernard Brault)

“In 2005-06, avian influenza was not being sustained in the wild population, it would die out,” Joly told CTVNews.ca in an interview this week.

“But this bug we’re dealing with seems to be different. It may be because there are (many) species that it can infect, (and) we’re seeing the virus over winter now, which is something that we didn’t see (before).”

Due to the high transmission rates in wild birds and the virus infecting other animals, Joly said he believes avian influenza could make a more aggressive jump to humans.

“My whole career, I’ve always thought influenzas will be the next pandemic, I was adamant, and of course, I was wrong; COVID happened,” Joly said. “But look all the previous pandemics…Despite all this distraction about coronaviruses, influenza is still the viruses we need to be watching.”

In terms of who is most at risk right now of contracting H5N1, federal officials say it’s people who work with poultry, hunt wild birds or are in contact with birds that eat small mammals.

LACK OF SURVEILLANCE LEAVES QUESTIONS

To understand how the virus is mutating, tracking positive infections in wild birds and other mammals is key, Provencher said.

A dashboard from the Canadians Wildlife Health Cooperative provides some answers to where infections spread among wildlife, but it’s only a snapshot of the thousands of animals that could have the virus, Joly said.

In an effort to provide more data, Environment Canada has “ramped up” surveillance of the bird flu over the last two years through antibody testing, Provencher said.

“This is giving us a peek into (wild bird) exposure in the last three to six months, and so that’s allowed us to figure out who’s been exposed (and if) we are building a herd immunity,” she said.

The work Provencher does is “tricky,” she said, because birds need to be tested for the virus the same way humans are: through a swab. This means catching, testing and releasing the bird.

“Just like COVID or the flu, you only shed the virus in this five- to seven-day window, so if you don’t have the bird in that exact five to seven days, they can test negative,” she said.

Since 2020, the program has swabbed more than 17,000 live and 10,000 dead or sick birds to get a better understanding of H5N1’s impact, Provencher said.

But funding pressure on government wildlife programs is a concern, she said. For scientists to understand the risks to animal species and humans, long-term monitoring and testing is needed, Provencher said.

“If we ramp down our ongoing surveillance, then we’ll have captured this big outbreak, but we won’t be able to understand whether some birds are becoming long-term reservoirs for the virus or if the virus is continuing to mutate into different subtypes,” Provencher said.

“The Centers for Disease Control across the world and the World Health Organization and the Organization for Animal Health, they’re all keeping an eye on it because it does have such implications for human health,” she said.

Denial of responsibility! My Droll is an automatic aggregator of Global media. In each content, the hyperlink to the primary source is specified. All trademarks belong to their rightful owners, and all materials to their authors. For any complaint, please reach us at – [email protected]. We will take necessary action within 24 hours.